A Global Map of Celiac Disease

This article focuses on the varying frequency of celiac disease in “time and space”. The information it contains is not only relevant for statistical purposes but also serves to formulate hypotheses on the factors which contribute to the development of this disease that is so widespread in modern society.

The development of simple but reliable diag-nostic methods making it possible to analyse the frequency of celiac disease in different cultures and regions has given a major boost to epidemiological research in this field. These methods – including the detection of anti-gliadin antibodies, anti-transglutaminase antibodies and anti-endomysial antibodies as well as the HLA test for genetic predisposition – require just a few drops of blood, which can also be analysed elsewhere (if, as is the case in some developing countries, the necessary laboratory equipment is not available on site). This international research has resulted in an interesting global map of celiac disease which we will now look at in a little more detail.

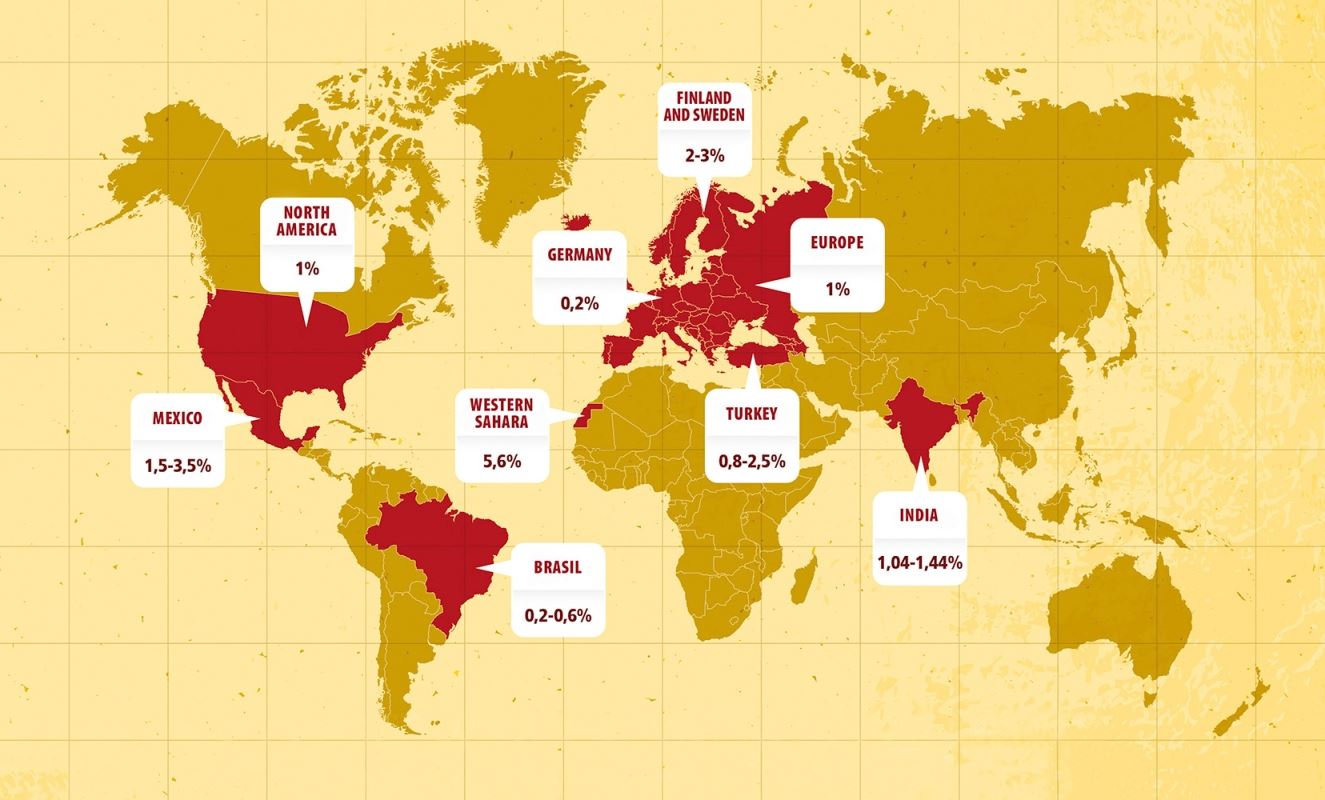

Celiac disease used to be considered a rare disease limited almost exclusively to the region of Europe and the age group of children. However, the first comprehensive tests, launched in the 1980s, have revealed a very different reality. Celiac disease is one of the most frequent of all lifelong diseases, affects children and adults in equal measure and is more common in women (ratio men/women = 1:1.5-2). In It-aly and generally in Europe where a great deal of research on celiac disease has been conducted there are variations in the rate of prevelance in the different countries. This can also be seen in the Americas, where the rate is only .2 to .6 % in Brazil but 1.5-3.5 % in Mexico 3.5 % in Mexico. As the genetic differences between these populations are very small, it can be assumed that these fluctuations in frequency are the result of still relatively unknown environmental factors such as child nutrition, intestinal infections and the typology of intestinal flora (known as “microbiome”). Other countries with populations of primarily European descent – such as the United States, Australia and Argentina – have also shown an average frequency of 1 %.

Celiac disease used to be considered a rare disease limited almost exclusively to the region of Europe and the age group of children. However, the first comprehensive tests, launched in the 1980s, have revealed a very different reality. Celiac disease is one of the most frequent of all lifelong diseases, affects children and adults in equal measure and is more common in women (ratio men/women = 1:1.5-2). In It-aly and generally in Europe where a great deal of research on celiac disease has been conducted there are variations in the rate of prevelance in the different countries. This can also be seen in the Americas, where the rate is only .2 to .6 % in Brazil but 1.5-3.5 % in Mexico 3.5 % in Mexico. As the genetic differences between these populations are very small, it can be assumed that these fluctuations in frequency are the result of still relatively unknown environmental factors such as child nutrition, intestinal infections and the typology of intestinal flora (known as “microbiome”). Other countries with populations of primarily European descent – such as the United States, Australia and Argentina – have also shown an average frequency of 1 %.

Sketch of a new epidemiology of celiac disease, characterized by growth in the traditional fields and spread into new regions of the world

Another worrying fact revealed by epidemi-ological research is that frequency of celiac disease is still on the rise in the West. In the United States, for example, the frequency has increased over the last 40 years from 2 cases per thousand to 10 cases per thousand (1 %). This alarming fact also indicates that environmental factors, such as the spread of ever more “toxic” cereals and shorter proving times for bread dough, play a decisive role.

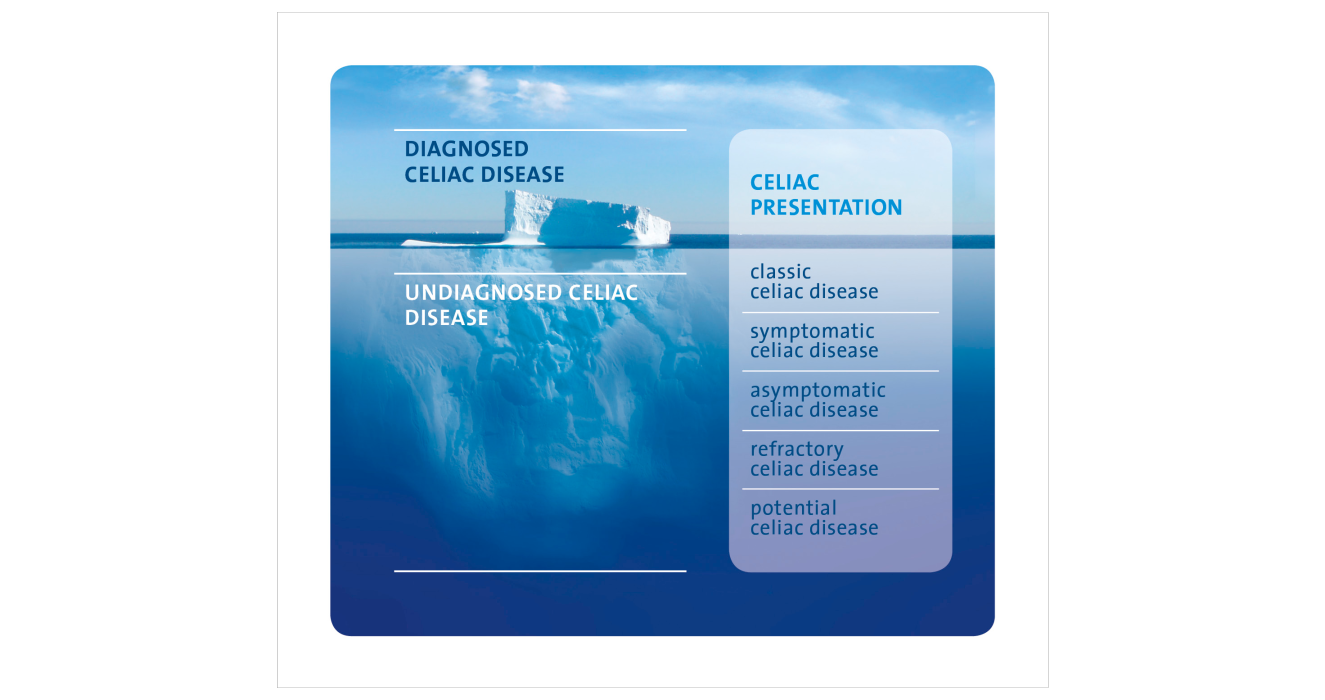

At the same time as this epidemiological research was being carried out, the concept of the “celiac iceberg” developed. This means that, despite an ongoing rise in diagnosed cases, the number of celiac sufferers diagnosed through their symptoms is still a long way below previous estimates of the total prevalence.

Approximately 70-80 % of all cases remain undiagnosed (representing the section of the iceberg below the water’s surface), in particular as sufferers show either ambiguous symptoms or no symptoms at all. In such situations there is a risk that patients may later suffer from complications as a result of not receiving dietary treatment for the disease.

In developing countries the epidemiological reality is far more concerning than in the Western world. First and foremost, the myth that celiac disease primarily affects Europeans has been debunked: research indicates that the frequency of the disease in North Africa, the Middle East and India is the same (around 1 %) as in Europe. Indeed, in one African people – the Sahrawi from the Western Sahara – celiac disease was shown to have an endemic presence of 6-7 % among children. The reasons for such a high frequency are unknown; however, it is believed that this specific situation may have been caused by a sudden change in the Sahrawi’s eating habits that saw them switch from a diet of mainly camel milk and camel meat to more European eating habits, including a drastic increase in their consumption of cereal products, as a result of Spanish colonisation. In developing countries, non-diagnosed cases of celiac disease can cause severe forms of protein-calorie malnutrition, which in turn increases the risk of other diseases and infant mortality. The lack of awareness among doctors about celiac disease and the limited availability of diagnostic tests mean that the diagnosed cases of the disease represent only a fraction of the total number of people affected. In India, for example, it is estimated that, as well as the few thousand diagnosed cases, there are between 5 and 10 million further celiac sufferers (a “celiac iceberg” that lies almost entire-ly below the water’s surface).

At the same time as this epidemiological research was being carried out, the concept of the “celiac iceberg” developed. This means that, despite an ongoing rise in diagnosed cases, the number of celiac sufferers diagnosed through their symptoms is still a long way below previous estimates of the total prevalence.

Approximately 70-80 % of all cases remain undiagnosed (representing the section of the iceberg below the water’s surface), in particular as sufferers show either ambiguous symptoms or no symptoms at all. In such situations there is a risk that patients may later suffer from complications as a result of not receiving dietary treatment for the disease.

In developing countries the epidemiological reality is far more concerning than in the Western world. First and foremost, the myth that celiac disease primarily affects Europeans has been debunked: research indicates that the frequency of the disease in North Africa, the Middle East and India is the same (around 1 %) as in Europe. Indeed, in one African people – the Sahrawi from the Western Sahara – celiac disease was shown to have an endemic presence of 6-7 % among children. The reasons for such a high frequency are unknown; however, it is believed that this specific situation may have been caused by a sudden change in the Sahrawi’s eating habits that saw them switch from a diet of mainly camel milk and camel meat to more European eating habits, including a drastic increase in their consumption of cereal products, as a result of Spanish colonisation. In developing countries, non-diagnosed cases of celiac disease can cause severe forms of protein-calorie malnutrition, which in turn increases the risk of other diseases and infant mortality. The lack of awareness among doctors about celiac disease and the limited availability of diagnostic tests mean that the diagnosed cases of the disease represent only a fraction of the total number of people affected. In India, for example, it is estimated that, as well as the few thousand diagnosed cases, there are between 5 and 10 million further celiac sufferers (a “celiac iceberg” that lies almost entire-ly below the water’s surface).

Considering this situation, it seems right to ask which strategy represents the most effective way of bringing such undiagnosed cases “to the surface”. So far, the strategy most commonly recommended has been to use the diagnostic tests on all persons who are “at risk”, for example relatives of individuals with celiac disease as well as individuals with autoimmune diseases or with symptoms that may indicate the presence of celiac disease (stunted growth, persistent intestinal problems, anaemia, etc.). This low-cost strategy, known as “case-finding”, can be justified from both an ethical and a financial point of view, but it is not particularly effective and diagnoses no more than 30 % of cases. Therefore, “universal” screening is gaining ground. In this case, blood tests are carried out on all children when they reach the age of compulsory education (6 years) in order to determine the presence of celiac antibodies. The effectiveness of this strategy may be linked to the fact that the child’s genetic predisposition is already assessed at birth (the HLA test, like other screening methods used on newborns, requires just a drop of blood), so antibody tests are carried out only on those children who tested positive for a genetic predisposition to the disease at birth.

In conclusion, it can be confirmed that the global map of celiac disease is far more densely “populated” than previously assumed. Health authorities both in the Western world and in developing countries must pay serious attention to this situation. Epidemiological research into celiac disease contributes to identifying the environmental factors that may be responsible for fluctuations in frequency. In practice, it is necessary to raise awareness of this “chamaeleon-like” disease as well as to develop possible mass screening strategies in order to bring the celiac iceberg, i.e. the many undiagnosed cases, as far as possible towards the surface.

In conclusion, it can be confirmed that the global map of celiac disease is far more densely “populated” than previously assumed. Health authorities both in the Western world and in developing countries must pay serious attention to this situation. Epidemiological research into celiac disease contributes to identifying the environmental factors that may be responsible for fluctuations in frequency. In practice, it is necessary to raise awareness of this “chamaeleon-like” disease as well as to develop possible mass screening strategies in order to bring the celiac iceberg, i.e. the many undiagnosed cases, as far as possible towards the surface.

Author

PROFESSOR CARLO CATASSI

- Professor for pediatrician at the Marche Poltechnic University (Italy)

- President of the Italian Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, years 2013-2016

- Coordinator of the Dr. Schär Advisory Board

References

- Catassi C, Gatti S, Fasano A “The New Epidemiology of Celiac Disease” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition, July 2014 Volume 59

www.drschaer-institute.com