The Low FODMAP Diet for Irritable Bowel Syndrome

IBS is a chronic and debilitating functional gastrointestinal disorder with research suggesting that it effects at least 10% of the UK, European and US population. [1,2]

Most IBS treatment is managed in primary care [3] with 1 in 12 consultations with a general practitioner (GP) being based around gastrointestinal problems and 46% of these being diagnosed with IBS. [3] However, GPs have little knowledge of the diagnostic criteria for IBS and often inappropriately refer for specialist consultations and/or prescribe a number of drugs. [4,5] Spiegel’s research suggested that despite clear Rome criteria for the diagnosis of IBS, over 70% of community practitioners still incorrectly treat IBS as a ‘diagnosis by exclusion’. [6]

In excess of 2.34 million people in the UK seek advice from their GP for IBS [4,5] and around 20% of these will be referred on to secondary gastroenterology care and 9% for surgical intervention, which constitutes a significant health care cost. [3] Indeed, in 2011 an audit of secondary care gastroenterology out patients in two district hospitals found that 14.3% of patients where being inappropriately referred for investigations: these patients had no red flags, a suspected diagnosis of IBS, were under the age of 45 and were costing in excess of £129,000 (> $217,300 US) per annum in secondary care consultations and investigations. The financial costs can be increased substantially when one considers that 47% of this group had already undergone previous secondary care investigations for IBS symptoms in the ‘revolving door’ of diagnosis and ineffective treatment. [7]

In excess of 2.34 million people in the UK seek advice from their GP for IBS [4,5] and around 20% of these will be referred on to secondary gastroenterology care and 9% for surgical intervention, which constitutes a significant health care cost. [3] Indeed, in 2011 an audit of secondary care gastroenterology out patients in two district hospitals found that 14.3% of patients where being inappropriately referred for investigations: these patients had no red flags, a suspected diagnosis of IBS, were under the age of 45 and were costing in excess of £129,000 (> $217,300 US) per annum in secondary care consultations and investigations. The financial costs can be increased substantially when one considers that 47% of this group had already undergone previous secondary care investigations for IBS symptoms in the ‘revolving door’ of diagnosis and ineffective treatment. [7]

INFO “RED FLAGS”

indicate that it is necessary to look for another initial cause.

The 2008 ‘IBS Costing Report Implementing NICE Guidance’ noted that significant savings could be made with a reduction in inappropriate secondary care input and an increased Between 25 to 45 million people in the US are affected by IBS. That is approximately 10-15% of the US population. 20 to 40% of all visits to a gastroenterologist are due to IBS focus on diet as a first line treatment option for IBS. [5] Yet, even up to 2007 there seemed to be limited evidence for the involvement of diet in IBS treatment. [8] However, subsequent documents have given more credibility to the dietary approach and in 2010 The British Dietetic Association produced a professional consensus statement into the dietetic management of IBS. [1]

In fact in the UK, we first started to hear about a new revolutionary diet for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in 2009 when a team from Guys & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and Kings College London began investigating Australian research into the Low Fermentable Carbohydrate Diet, also known as the ‘Low FODMAP Diet’.

In fact in the UK, we first started to hear about a new revolutionary diet for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in 2009 when a team from Guys & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and Kings College London began investigating Australian research into the Low Fermentable Carbohydrate Diet, also known as the ‘Low FODMAP Diet’.

INFO FODMAP

The term 'FODMAP' is an acronym derived from a list of foods that have a visible physiological effect on patients with IBS: Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides And Polyols.

Studies about Low-FODMAP Diet

The diet was developed by a team from Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and started to gain prominence following publication of research in 2008 showing that dietary fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) did indeed act as symptom triggers in IBS patients. [9] Since then there have been three randomized controlled trials each of which has shown a clear benefit of using the Low FODMAP diet. [10–12] and this data, along with three prospective uncontrolled trials [13–15] and two further retrospective trials [16,17] has led to fermentable carbohydrate restriction becoming an important consideration for future national and international guidelines with in IBS treatment. Research repeatedly indicates that patients using this diet report a marked improvement in bloating, flatulence, abdominal pain, urgency and altered stool output, with up to 70% of patients reporting benefit. [2] Indeed, in 2010 the Low FODMAP diet entered the UK British Dietetic Association IBS Guidelines [18] and in 2011 the diet was adopted by the Australian National Therapeutic Guidelines. [19]

Where can FODMAPs be found?

FODMAPs appear in a range of foods including wheat, certain fruit and vegetables and some milk-based products. In Western Europe oligo-saccharides such as ‘fructans’ and the mono-saccharide, ‘fructose’, are the most common FODMAPs in the diet, with wheat thought to be the largest contributor of fructans in the UK. [20]

Download

The mechanisms by which these fermentable carbohydrates provoke gut symptoms are due to two underlying physiological processes: first, these carbohydrates are indigestible and subsequently fermented by the bacteria in the colon which leads to gas production. This gas can alter the luminal environment and cause visceral hypersensitivity in those who are susceptible to gut pain. [11] Second, there is an osmotic effect whereby fermentable carbohydrates increase water delivery to the proximal colon leading to altered bowel movements. [21]

The low-FODMAP diet differentiates between three phases

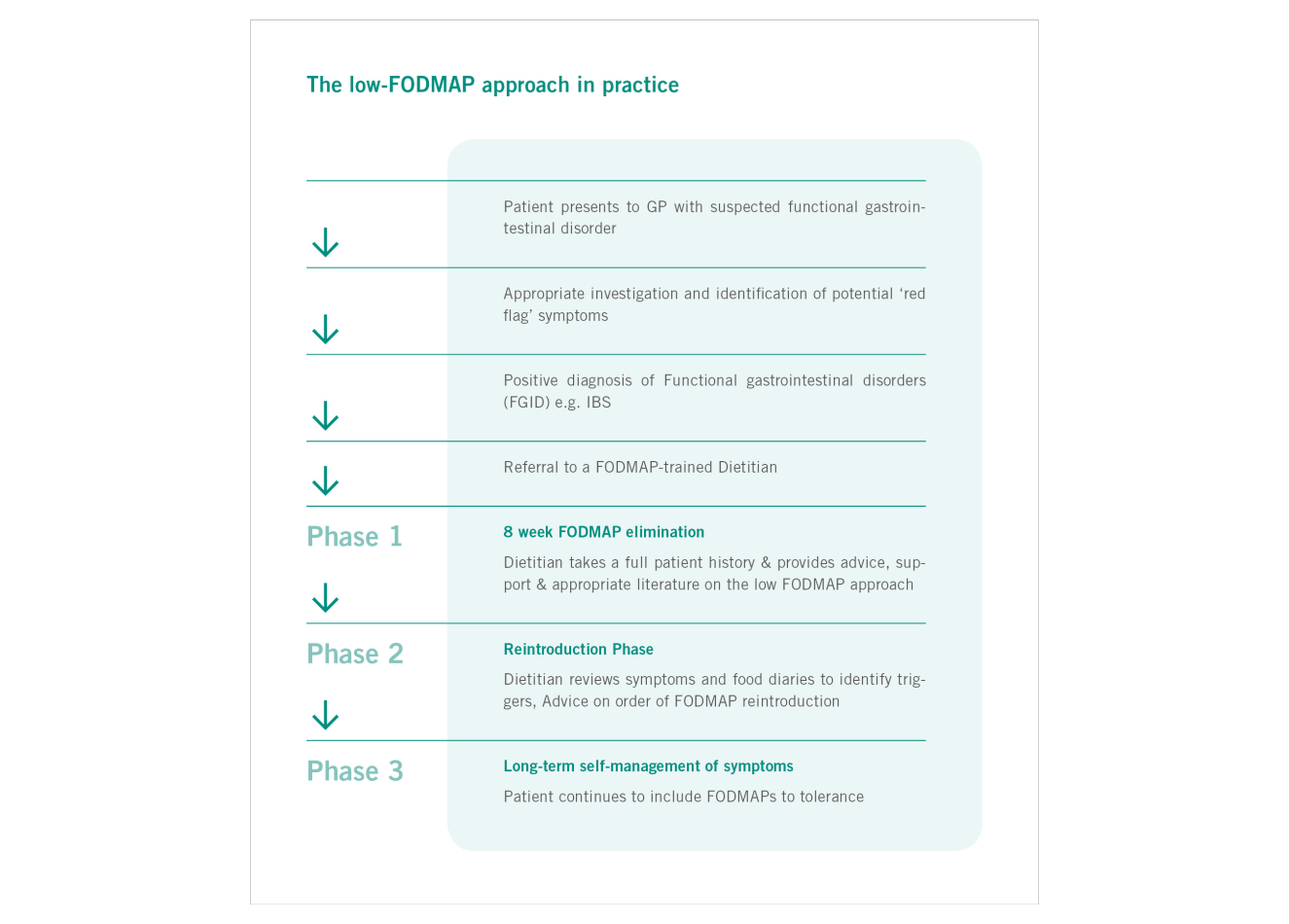

Following the diagnosis of a functional bowel disorder within a typical primary care setting, the implementation of the low FODMAP approach consists of 3 main stages (see figure 1).

Prior to the first exclusion phase, hydrogen breath tests may be used to test for the presence of fructose and lactose malabsorption. The results may allow for a less restrictive diet if the FODMAPs fructose and/or lactose are found to be well tolerated. The first phase involves complete removal of FODMAP containing foods for a period of 8 weeks under the advice and supervision of a suitably qualified Dietitian, trained in the low FODMAP approach.

Following the 8 week exclusion phase, a thorough dietetic review of symptoms and food diaries will guide the reintroduction phase. Depending on symptoms, advice will be provided on the appropriate order and quantity of reintroduction of FODMAP-containing foods.

The long-term self-management of symptoms is managed by consuming FODMAP foods to tolerance. The ability to empower patients to take control of their own gut symptoms in the long term and the subsequent de-clinicalization of their condition is viewed as a great advantage of the low FODMAP approach.

Prior to the first exclusion phase, hydrogen breath tests may be used to test for the presence of fructose and lactose malabsorption. The results may allow for a less restrictive diet if the FODMAPs fructose and/or lactose are found to be well tolerated. The first phase involves complete removal of FODMAP containing foods for a period of 8 weeks under the advice and supervision of a suitably qualified Dietitian, trained in the low FODMAP approach.

Following the 8 week exclusion phase, a thorough dietetic review of symptoms and food diaries will guide the reintroduction phase. Depending on symptoms, advice will be provided on the appropriate order and quantity of reintroduction of FODMAP-containing foods.

The long-term self-management of symptoms is managed by consuming FODMAP foods to tolerance. The ability to empower patients to take control of their own gut symptoms in the long term and the subsequent de-clinicalization of their condition is viewed as a great advantage of the low FODMAP approach.

Other applications

Research has followed [22] which shows that the diet is not only useful in IBS, but that it could also be helpful in ameliorating the functional gut symptoms in other conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease. [16] Potential benefits in enteral feeding diarrhea [23,24] and reducing stool frequency in high output ileostomy or in ileal pouch patients, is also reported although more data is required. [25]

Benefits of FODMAPs

While the benefits of this diet are now well documented, the significance of fermentable carbohydrate withdrawal on the health and nutritional status of the patient and whether there are any long term implications is still not clear. Indeed, fermentable carbohydrates help to increase stool bulk, enhance calcium absorption, modulate immune function and help to encourage the growth and functioning of some beneficial microbial groups such as bifidobacteria. Therefore, more studies are needed in this area. [2]

Conclusion

Historically IBS patients have been both expensive and difficult to treat, costing the UK in excess of £45.6 million ( > 76.5 Million US Dollars) in 2003. [26] Indeed, IBS patients incur 51% more total costs per year than a non IBS control group. [27] However, the Low FODMAP diet finally gives a viable alternative therapy for this chronic and debilitating condition and should be seriously considered as a treatment option for any intractable IBS patients.

Author

MARIANNE WILLIAMS, BSC HONS, RD, MSC ALLERGY

Marianne Williams is a IBS and allergy specialist dietitian who works for Somerset Partnership NHS Trust. Her focus on innovation has led to the formation of a new professional role within the NHS, the ‘Specialist Community Gastroenterology Dietitian’, and the creation of the first UK ‘Dietetic-Led Primary Care Gastroenterology Clinic’. This award winning service has an over 75% success rate using a range of specialist evidence based dietary interventions for adult patients with IBS and gastrointestinal allergy with over 63% of positive responders using the highly successful Low FODMAP diet. The clinic is saving considerable money for the NHS by preventing non-red flag referrals into secondary care and by providing an effective alternative pathway for both primary and secondary care clinicians.

Marianne Williams is a IBS and allergy specialist dietitian who works for Somerset Partnership NHS Trust. Her focus on innovation has led to the formation of a new professional role within the NHS, the ‘Specialist Community Gastroenterology Dietitian’, and the creation of the first UK ‘Dietetic-Led Primary Care Gastroenterology Clinic’. This award winning service has an over 75% success rate using a range of specialist evidence based dietary interventions for adult patients with IBS and gastrointestinal allergy with over 63% of positive responders using the highly successful Low FODMAP diet. The clinic is saving considerable money for the NHS by preventing non-red flag referrals into secondary care and by providing an effective alternative pathway for both primary and secondary care clinicians.

References

- McKenzie Y. A., Alder A., Anderson W., Wills A., Goddard L., Gulia P. et al. British Dietetic Association evidence-based guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. 2012 Jun;25(3):260–274

- Staudacher H. M., Irving P. M., Lomer M. C., Whelan K. Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Jan 21

- Thompson W. G. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46(1):78–82

- Bellini M. T. C., Costa F., Biagi S., Stasi C., El Punta A., Monicelli P., Mumolo M. G., Ricchiuti A., Bruzzi P., Marchi S. The general practitioners approach to irritable bowel syndrome: From intention to practice. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2005;37(12):934–939

- NICE. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Costing report implementing NICE guidance. London February 2008

- Spiegel B. Is irritable bowel syndrome a diagnosis of exclusion? A survey of primary care providers, gastroenterologists and IBS experts. Am J Gastroenterology. 2010;105(4):848–858

- Greig E. Audit of gastroenterology outpatients clinic data for May 2011

- Halpert A., Dalton C. B., Palsson O., Morris C., Hu Y., Bangdiwala S. et al. What patients know about irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and what they would like to know. National Survey on Patient Educational Needs in IBS and development and validation of the Patient Educational Needs Questionnaire (PEQ). Am J Gastroenterol. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2007 Sep;102(9):1972–1982

- Shepherd S. J. P. F, Muir J. G., Gibson P. R. Dietary Triggers of Abdominal Symptoms in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Randomized Placebo-Controlled Evidence. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;6(7):765–771

- Staudacher H. M., Lomer M. C., Anderson J. L., Barrett J. S., Muir J. G., Irving P. M. et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. The Journal of nutrition. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2012 Aug;142(8):1510–1518

- Ong D.K. M. S., Barrett J. S., Shepherd S. J., Irving P. M., Biesiekierski J. R., Smith S., Gibson P. R., Muir J. G. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2010;25(8):1366–1373

- Halmos E. P., Power V. A., Shepherd S. J., Gibson P. R., Muir J. G. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2014 Jan;146(1):67–75 e5

- de Roest R. H., Dobbs B. R., Chapman B. A., Batman B., O'Brien L. A., Leeper J. A. et al. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract. [Evaluation Studies Observational Study]. 2013 Sep;67(9):895–903

- Mazzawi T., Hausken T., Gundersend D., El-Salhy M. Effects of dietary guidance on the symptoms, quality of life and habitual dietary intake of patients with irritiable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:845–852

- Wilder-Smith C., Materna A., Wermelinger C., Schuler J. Fructose and lactose intolerance and malabsorption testing: the relationship with symptoms in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:1074–1083

- Gearry R., Irving P. M., Barrett J. S., Nathan D. M., Shepherd S. J., Gibson P. R. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease - a pilot study. Journal of Crohns and Colitis. 2009;3(1):8–14

- Ostgaard H., Hausken T., Gundersend D., El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:1382–1390

- British Dietetic Association. UK evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietetic management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in adults. Birmingham September 2010

- Government NSW, Australia. Therapeutic Diet Specifications for Adult Inpatients. Chatswood, New South Wales, Australia: Agency for Clinical Innovation; 2011

- Gibson P. R., Shepherd S. J. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review]. 2010 Feb;25(2):252–258

- Barrett J. S., Gearry R. B., Muir J. G., Irving P. M., Rose R., Rosella O. et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2010 Apr;31(8):874–882

- Staudacher H. M., Whelan K., Irving P. M., Lomer M. C. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2011 Oct;24(5):487–495

- Barrett J. S., Shepherd S. J., Gibson P. R. Strategies to Manage Gastrointestinal Symptoms Complicating Enteral Feeding. Journal of Parenteral & Enteral Nutrition. 2009;33(1):21–26

- Halmos E. P. M. J., Barrett J. S., Deng M., Shepherd S. J., Gibson P.R. Diarrhoea during enteral nutrition is predicted by the poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAP) content of the formula. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(7):925–933

- Croagh C., Shepherd S. J., Berryman M., Muir J. G., Gibson P. R. Pilot study on the effect of reducing dietary FODMAP intake on bowel function in patients without a colon. Inflammatory bowel diseases. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2007 Dec;13(12):1522–1528

- Longstreth G. F., Thompson W. G., Chey W. D., Houghton L. A., Mearin F., Spiller R. C. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. [Review]. 2006 Apr;130(5):1480–1491

- Maxion-Bergemann S. T. F., Abel F., Bergemann R. Costs of irritable bowel syndrome in the UK and US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24(1):21–37

www.drschaer-institute.com