What is the low-FODMAP diet?

FODMAPs are common short-chain, fermentable carbohydrates that are widespread throughout a number of food groups, including wheat. Research has shown that FODMAPs can provoke functional gastrointestinal symptoms in susceptible individuals [1,2].

The abbreviation FODMAPs stands for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols. This group of short-chain, fermentable carbohydrates includes fructans, which are predominantly found in wheat. A diet low in FODMAPs has been found to be effective in the management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [1,3,4]. The mechanisms by which these fermentable carbohydrates provoke gut symptoms are due to two underlying physiological processes: firstly, they are indigestible and subsequently fermented by the bacteria in the colon, which leads to gas production. The resulting gas can alter the gut environment and cause hypersensitivity in those who are susceptible to gut pain [1]. Secondly, there is an osmotic effect whereby fermentable carbohydrates increase water delivery to the colon leading to altered bowel habit [2].

Only introduce the diet under professional guidance

Despite the benefits, research suggests that this diet can have a detrimental effect on the gut bacteria [4] and may lack in calcium, and hence this diet is only to be used for 8 weeks at which point all removed foods must be reintroduced to tolerance in a stepwise manner. So far research shows this diet to be very successful when counselling is provided by a trained dietitian [5,6]. Patients should be discouraged from attempting to follow a low FODMAP diet without appropriate support and information.

Which FODMAPs are found in which foods?

This fact sheet shows which FODMAPs you can find in which foods.

Download

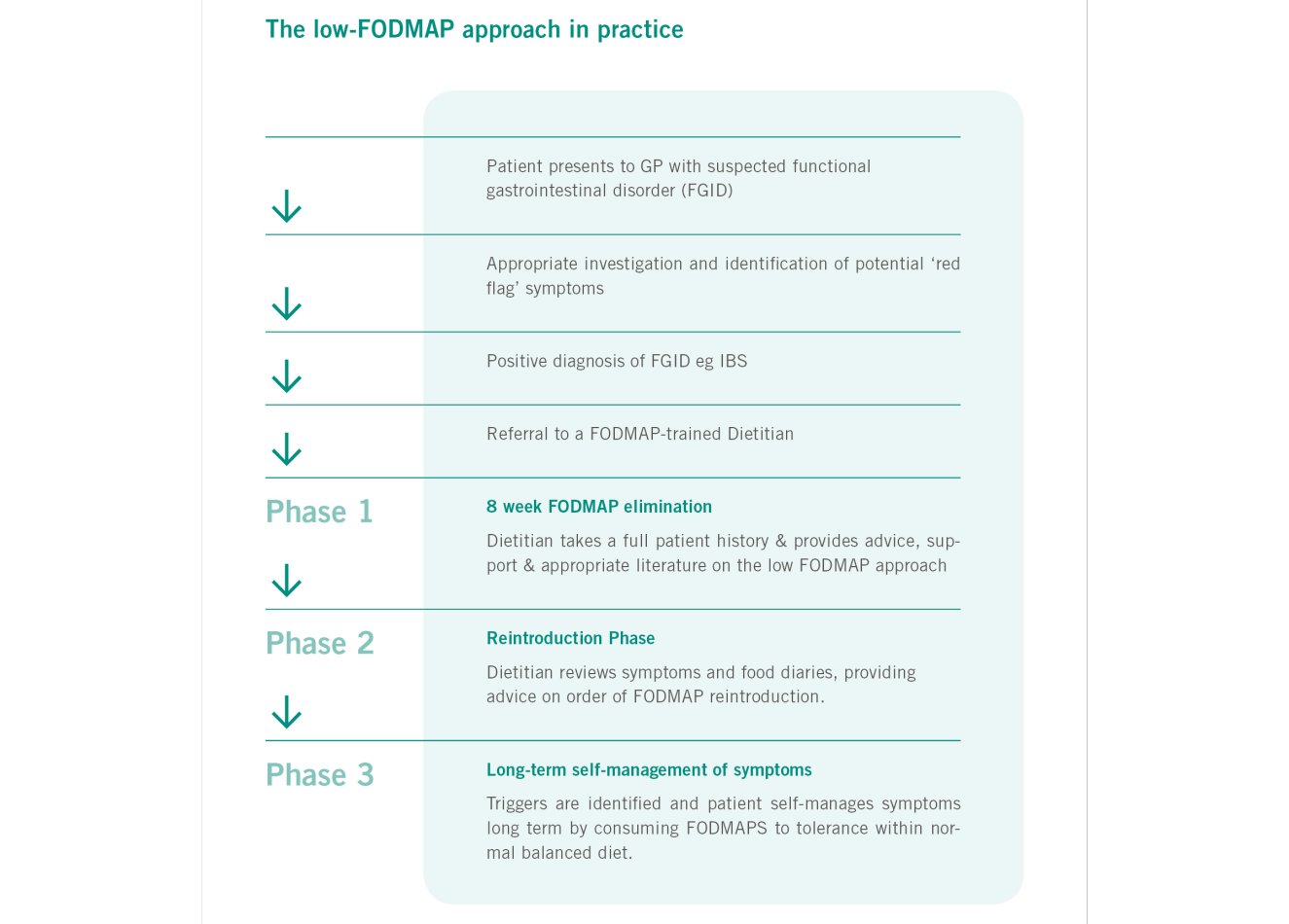

A flow-diagram describing the implementation of the low FODMAP diet.

A low-FODMAP diet for IBS

There have been three randomized controlled trials published showing a clear benefit of using the Low-FODMAP diet for IBS [1,3,4] and this data, along with three prospective uncontrolled trials [8-10] and two further retrospective trials [7,8], has led to fermentable carbohydrate restriction becoming an important treatment option for patients with IBS. Research indicates that patients using this diet report a marked improvement in symptoms, with up to 70% of patients reporting benefit [9]. The Low-FODMAP Diet is now noted on the UK NICE Guidance [10] and in the British Dietetic Association IBS Guidance [11].

References

- Ong DK MS, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Irving PM, Biesiekierski JR, Smith S, Gibson PR, Muir JG,. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2010;25(8):1366-73

- Murray K, Wilkinson-Smith V, Hoad C, Costigan C, Cox E, Lam C, et al. Differential effects of FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols) on small and large intestinal contents in healthy subjects shown by MRI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(1):110-9.

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):67-75 e5.

- Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Anderson JL, Barrett JS, Muir JG, Irving PM, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. The Journal of nutrition. 2012;142(8):1510-8.

- Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MC. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(5):487-95.

- Gibson PR, Barrett JS, Muir JG. Functional bowel symptoms and diet. Intern Med J. 2013;43(10):1067-74.

- Gearry R, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease - a pilot study. Journal of Crohns and Colitis. 2009;3(1):8-14

- Ostgaard H, Hausken T, Gundersend D, El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:1382-90.

- Staudacher HM, Irving PM, Lomer MC, Whelan K. Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014.

- Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MC. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(5):487-95.

- Gibson PR, Barrett JS, Muir JG. Functional bowel symptoms and diet. Intern Med J. 2013;43(10):1067-74.

Further information on this topic

Studies

3

Show all

Evidence for the Presence of Non-Coeliac Gluten Sensitivity in Patients with Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Results from a Multicenter Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Gluten Challenge

Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is a syndrome characterised by intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms related to the ingestion of gluten-containing food. Currently, available blood tests and histology do not help towards making the differential diagnosis, hence response to a gluten free diet in the absence of coeliac disease (CD) or wheat allergy (WA) is the fundamental principal of diagnosis for NCGS. Unfortunately, the placebo effect, in addition to the presence of other active compounds within wheat, e.g amylase trypsin inhibitors (ATIs), and FODMAPs, may act as confounding factors when analysing the impact of gluten withdrawal amongst potential NCGS sufferers. A correct diagnosis is essential in order to avoid unnecessary dietary restriction, provide effective treatment options, and to reduce the need for drugs in order to manage the symptoms of patients reporting functional bowel disorders including IBS.

The aim of this study was to identify patients with NCGS from those reporting an improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms whilst following a gluten free diet (GFD), through a double-blind placebo-controlled gluten challenge with crossover. The study was carried out in 15 gastrointestinal out-patients centres in Italy. The study enrolled 140 adult patients routinely attending gastrointestinal outpatient clinics and meeting the Rome III criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. All were following a gluten-containing diet and had negative IgA anti-tTG, normal total IgA and negative IgE mediated WA. Amongst patients with high clinical suspicion of CD, a duodenal biopsy was also performed in order to identify any seronegative patients.

Phase one of the trial investigated subject response to a GFD. Symptoms and quality of life were evaluated using a series of 10cm visual analogue scales (VASs) and a SF36 questionnaire. Following this initial evaluation, patients were asked to follow a GFD for 3 weeks. Subjects were provided with detailed information and support regarding the diet by an expert nutritionist. At the end of phase 1, patients repeated the VASs and SF36 questionnaire. Only those patients reporting a significant improvement in well-being (VAS ≥ 3cm, n=101) were defined as ‘gluten responsive’ and were enrolled in to phase 2 of the study.

Gluten responsive patients were asked to maintain their strict GFD for phase 2 of the trial (placebo-controlled double-blind gluten challenge with crossover). Ninety eight subjects were enrolled in this phase of the study (3 subjects refused to proceed owing to fear of symptom relapse during challenge). Patients were randomised to receive either purified gluten capsules (5.6g/ day, equivalent to 80g of dried pasta) or the same volume of placebo capsules (rice starch) for 7 days. A 7 day washout period was scheduled between the cross-over periods, hence the total duration of phase 2 was 21 days (subjects followed a gluten free diet throughout). Subjects completed the VASs and SF36 questionnaire at the end of each 7 day period (gluten challenge, cross over and placebo). Overall, subjects reported a greater deterioration in well-being during the gluten challenge rather than during placebo administration (p=0.05). Twenty eight of the randomised patients were identified as being ‘positive’ to the DBPCC (ie with symptomatic relapse during gluten ingestion) and 69 were found to be ‘negative’ to the DBPCC (ie without any symptomatic reaction during gluten administration). No demographic, clinical or biochemical factors were found to be associated with the gluten challenge response. Among positive patients, there appeared to be no significant effect of capsule sequence. Notably, 14 of the 28 positive patients were also considered to be placebo responsive, indicating a significant ‘placebo effect’, as would be expected.

Overall, 14% of the 98 randomised ‘gluten responsive’ patients showed a symptomatic relapse during the blind placebo-controlled gluten challenge (without concurrent response to placebo) and accordingly can be defined as patients with NCGS. This finding confirms that gluten ingestion may induce gastrointestinal symptoms in a sub-set of patients with functional bowel disorders. This study is the first to assess the performance of the Salerno Experts’ diagnostic criteria1 for NCGS in a clinical setting. The large number of patients responsive to a GFD (75%) but negative to gluten challenge is interesting, a possible placebo affect is likely to account for some of this discrepancy, however many patients might also be sensitive to other unspecified wheat components, e.g ATIs or FODMAPs.

Elli L, Tomba C, Branchi R et al

Nutrients 2016; 8: 84; doi:10.3390/nu8020084

The aim of this study was to identify patients with NCGS from those reporting an improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms whilst following a gluten free diet (GFD), through a double-blind placebo-controlled gluten challenge with crossover. The study was carried out in 15 gastrointestinal out-patients centres in Italy. The study enrolled 140 adult patients routinely attending gastrointestinal outpatient clinics and meeting the Rome III criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. All were following a gluten-containing diet and had negative IgA anti-tTG, normal total IgA and negative IgE mediated WA. Amongst patients with high clinical suspicion of CD, a duodenal biopsy was also performed in order to identify any seronegative patients.

Phase one of the trial investigated subject response to a GFD. Symptoms and quality of life were evaluated using a series of 10cm visual analogue scales (VASs) and a SF36 questionnaire. Following this initial evaluation, patients were asked to follow a GFD for 3 weeks. Subjects were provided with detailed information and support regarding the diet by an expert nutritionist. At the end of phase 1, patients repeated the VASs and SF36 questionnaire. Only those patients reporting a significant improvement in well-being (VAS ≥ 3cm, n=101) were defined as ‘gluten responsive’ and were enrolled in to phase 2 of the study.

Gluten responsive patients were asked to maintain their strict GFD for phase 2 of the trial (placebo-controlled double-blind gluten challenge with crossover). Ninety eight subjects were enrolled in this phase of the study (3 subjects refused to proceed owing to fear of symptom relapse during challenge). Patients were randomised to receive either purified gluten capsules (5.6g/ day, equivalent to 80g of dried pasta) or the same volume of placebo capsules (rice starch) for 7 days. A 7 day washout period was scheduled between the cross-over periods, hence the total duration of phase 2 was 21 days (subjects followed a gluten free diet throughout). Subjects completed the VASs and SF36 questionnaire at the end of each 7 day period (gluten challenge, cross over and placebo). Overall, subjects reported a greater deterioration in well-being during the gluten challenge rather than during placebo administration (p=0.05). Twenty eight of the randomised patients were identified as being ‘positive’ to the DBPCC (ie with symptomatic relapse during gluten ingestion) and 69 were found to be ‘negative’ to the DBPCC (ie without any symptomatic reaction during gluten administration). No demographic, clinical or biochemical factors were found to be associated with the gluten challenge response. Among positive patients, there appeared to be no significant effect of capsule sequence. Notably, 14 of the 28 positive patients were also considered to be placebo responsive, indicating a significant ‘placebo effect’, as would be expected.

Overall, 14% of the 98 randomised ‘gluten responsive’ patients showed a symptomatic relapse during the blind placebo-controlled gluten challenge (without concurrent response to placebo) and accordingly can be defined as patients with NCGS. This finding confirms that gluten ingestion may induce gastrointestinal symptoms in a sub-set of patients with functional bowel disorders. This study is the first to assess the performance of the Salerno Experts’ diagnostic criteria1 for NCGS in a clinical setting. The large number of patients responsive to a GFD (75%) but negative to gluten challenge is interesting, a possible placebo affect is likely to account for some of this discrepancy, however many patients might also be sensitive to other unspecified wheat components, e.g ATIs or FODMAPs.

Elli L, Tomba C, Branchi R et al

Nutrients 2016; 8: 84; doi:10.3390/nu8020084

Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

A low FODMAP (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides And Polyols) diet reduces symptoms of IBS, but reduction of potential prebiotic and fermentative effects might adversely affect the colonic microenvironment. The effects of a low FODMAP diet with a typical Australian diet on biomarkers of colonic health were compared in a single-blinded, randomised, cross-over trial.

DESIGN:

Twenty-seven IBS and six healthy subjects were randomly allocated one of two 21-day provided diets, differing only in FODMAP content (mean (95% CI) low 3.05 (1.86 to 4.25) g/day vs Australian 23.7 (16.9 to 30.6) g/day), and then crossed over to the other diet with ≥21-day washout period. Faeces passed over a 5-day run-in on their habitual diet and from day 17 to day 21 of the interventional diets were pooled, and pH, short-chain fatty acid concentrations and bacterial abundance and diversity were assessed.

RESULTS:

Faecal indices were similar in IBS and healthy subjects during habitual diets. The low FODMAP diet was associated with higher faecal pH (7.37 (7.23 to 7.51) vs 7.16 (7.02 to 7.30); p=0.001), similar short-chain fatty acid concentrations, greater microbial diversity and reduced total bacterial abundance (9.63 (9.53 to 9.73) vs 9.83 (9.72 to 9.93) log10 copies/g; p<0.001) compared with the Australian diet. To indicate direction of change, in comparison with the habitual diet the low FODMAP diet reduced total bacterial abundance and the typical Australian diet increased relative abundance for butyrate-producing Clostridium cluster XIVa (median ratio 6.62; p<0.001) and mucus-associated Akkermansia muciniphila (19.3; p<0.001), and reduced Ruminococcus torques.

CONCLUSIONS:

Diets differing in FODMAP content have marked effects on gut microbiota composition. The implications of long-term reduction of intake of FODMAPs require elucidation.

Resource: Gut. 2014 Jul 12. pii: gutjnl-2014-307264. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307264. [Epub ahead of print]

Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG.

OBJECTIVE:

A low FODMAP (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides And Polyols) diet reduces symptoms of IBS, but reduction of potential prebiotic and fermentative effects might adversely affect the colonic microenvironment. The effects of a low FODMAP diet with a typical Australian diet on biomarkers of colonic health were compared in a single-blinded, randomised, cross-over trial.

DESIGN:

Twenty-seven IBS and six healthy subjects were randomly allocated one of two 21-day provided diets, differing only in FODMAP content (mean (95% CI) low 3.05 (1.86 to 4.25) g/day vs Australian 23.7 (16.9 to 30.6) g/day), and then crossed over to the other diet with ≥21-day washout period. Faeces passed over a 5-day run-in on their habitual diet and from day 17 to day 21 of the interventional diets were pooled, and pH, short-chain fatty acid concentrations and bacterial abundance and diversity were assessed.

RESULTS:

Faecal indices were similar in IBS and healthy subjects during habitual diets. The low FODMAP diet was associated with higher faecal pH (7.37 (7.23 to 7.51) vs 7.16 (7.02 to 7.30); p=0.001), similar short-chain fatty acid concentrations, greater microbial diversity and reduced total bacterial abundance (9.63 (9.53 to 9.73) vs 9.83 (9.72 to 9.93) log10 copies/g; p<0.001) compared with the Australian diet. To indicate direction of change, in comparison with the habitual diet the low FODMAP diet reduced total bacterial abundance and the typical Australian diet increased relative abundance for butyrate-producing Clostridium cluster XIVa (median ratio 6.62; p<0.001) and mucus-associated Akkermansia muciniphila (19.3; p<0.001), and reduced Ruminococcus torques.

CONCLUSIONS:

Diets differing in FODMAP content have marked effects on gut microbiota composition. The implications of long-term reduction of intake of FODMAPs require elucidation.

Resource: Gut. 2014 Jul 12. pii: gutjnl-2014-307264. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307264. [Epub ahead of print]

Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG.

A Diet Low in FODMAPs Reduces Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Abstract

Background & Aims: A diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) often is used to manage functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), yet there is limited evidence of its efficacy, compared with a normal Western diet. We investigated the effects of a diet low in FODMAPs compared with an Australian diet, in a randomized, controlled, single-blind, cross-over trial of patients with IBS.

Methods: In a study of 30 patients with IBS and 8 healthy individuals (controls, matched for demographics and diet), we collected dietary data from subjects for 1 habitual week. Participants then randomly were assigned to groups that received 21 days of either a diet low in FODMAPs or a typical Australian diet, followed by a washout period of at least 21 days, before crossing over to the alternate diet. Daily symptoms were rated using a 0- to 100-mm visual analogue scale. Almost all food was provided during the interventional diet periods, with a goal of less than 0.5 g intake of FODMAPs per meal for the low-FODMAP diet. All stools were collected from days 17–21 and assessed for frequency, weight, water content, and King's Stool Chart rating.

Results: Subjects with IBS had lower overall gastrointestinal symptom scores (22.8; 95% confidence interval, 16.7–28.8 mm) while on a diet low in FODMAPs, compared with the Australian diet (44.9; 95% confidence interval, 36.6–53.1 mm; P < .001) and the subjects' habitual diet. Bloating, pain, and passage of wind also were reduced while IBS patients were on the low-FODMAP diet. Symptoms were minimal and unaltered by either diet among controls. Patients of all IBS subtypes had greater satisfaction with stool consistency while on the low-FODMAP diet, but diarrhea-predominant IBS was the only subtype with altered fecal frequency and King's Stool Chart scores.

Conclusions: In a controlled, cross-over study of patients with IBS, a diet low in FODMAPs effectively reduced functional gastrointestinal symptoms. This high-quality evidence supports its use as a first-line therapy.

Resource: Gastroenterology Volume 146, Issue 1 , Pages 67-75.e5, January 2014

Emma P. Halmos, Victoria A. Power, Susan J. Shepherd, Peter R. Gibson, Jane G. Muir

Background & Aims: A diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) often is used to manage functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), yet there is limited evidence of its efficacy, compared with a normal Western diet. We investigated the effects of a diet low in FODMAPs compared with an Australian diet, in a randomized, controlled, single-blind, cross-over trial of patients with IBS.

Methods: In a study of 30 patients with IBS and 8 healthy individuals (controls, matched for demographics and diet), we collected dietary data from subjects for 1 habitual week. Participants then randomly were assigned to groups that received 21 days of either a diet low in FODMAPs or a typical Australian diet, followed by a washout period of at least 21 days, before crossing over to the alternate diet. Daily symptoms were rated using a 0- to 100-mm visual analogue scale. Almost all food was provided during the interventional diet periods, with a goal of less than 0.5 g intake of FODMAPs per meal for the low-FODMAP diet. All stools were collected from days 17–21 and assessed for frequency, weight, water content, and King's Stool Chart rating.

Results: Subjects with IBS had lower overall gastrointestinal symptom scores (22.8; 95% confidence interval, 16.7–28.8 mm) while on a diet low in FODMAPs, compared with the Australian diet (44.9; 95% confidence interval, 36.6–53.1 mm; P < .001) and the subjects' habitual diet. Bloating, pain, and passage of wind also were reduced while IBS patients were on the low-FODMAP diet. Symptoms were minimal and unaltered by either diet among controls. Patients of all IBS subtypes had greater satisfaction with stool consistency while on the low-FODMAP diet, but diarrhea-predominant IBS was the only subtype with altered fecal frequency and King's Stool Chart scores.

Conclusions: In a controlled, cross-over study of patients with IBS, a diet low in FODMAPs effectively reduced functional gastrointestinal symptoms. This high-quality evidence supports its use as a first-line therapy.

Resource: Gastroenterology Volume 146, Issue 1 , Pages 67-75.e5, January 2014

Emma P. Halmos, Victoria A. Power, Susan J. Shepherd, Peter R. Gibson, Jane G. Muir

Evidence for the Presence of Non-Coeliac Gluten Sensitivity in Patients with Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Results from a Multicenter Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Gluten Challenge

Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is a syndrome characterised by i...

Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

A low FODMAP (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Di...

A Diet Low in FODMAPs Reduces Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Abstract

Background & Aims: A diet low in fermentable oligosacchari...

www.drschaer-institute.com