Diagnosing coeliac disease

Diagnosis of coeliac disease is based on four pillars. It is essential that patients follow a gluten-containing diet both before and during the diagnostic procedure.

The four pillars underpinning a diagnosis of coeliac disease, are:

- Clinical history

- Serology

- Histology

- Improvement of symptoms and antibody response to a gluten-free diet

I. Clinical history

Clinical history includes both personal and family medical history in addition to a dietary history that specifically focuses on foods that contain gluten. Clinical symptoms are also monitored in this step, for example bowel habits, weight loss, abdominal bloating, abdominal pain, nausea and growth disorders in children. Extraintestinal symptoms such as fatigue, bone/joint pain and headaches/migraine are also important factors to consider here.

II. Serological tests

Serological testing for coeliac disease involves the identification of immunoglobulin A tissue transglutaminase (IgA tTG) antibodies and specific endomysial antibodies (EMA). Total IgA should be determined in order to rule out IgA deficiency and reduce the risk of a false negative result. In patients with known IgA deficiency, immunoglobulin G (IgG) EMA, IgG deaminated gliadin peptide (DGP) or IgG tTG may be used in order to support the diagnosis [1,2]. It is essential that patients consume a gluten containing diet prior to and during diagnostic investigation as results may normalise on a gluten-free diet.

HLA typing

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DQ2/DQ8 testing may be considered within the diagnostic work-up for patients within specialist settings. The diagnostic value of HLA genotyping within this patient group, revolves around it’s high negative predictive value – a negative result indicating that a patient is highly unlikely to have coeliac disease (less than 1% of patients with coeliac disease do not carry these alleles [3]). However, the positive predictive value of value of HLA genotyping is very low, since a up to 40% of the general population also carry genes encoding HLA DQ2/DQ8 [4]. HLA testing may therefore be useful for patients where the diagnosis is equivocal, or for those who have already embarked on a gluten free diet and choose not to have a gluten challenge.

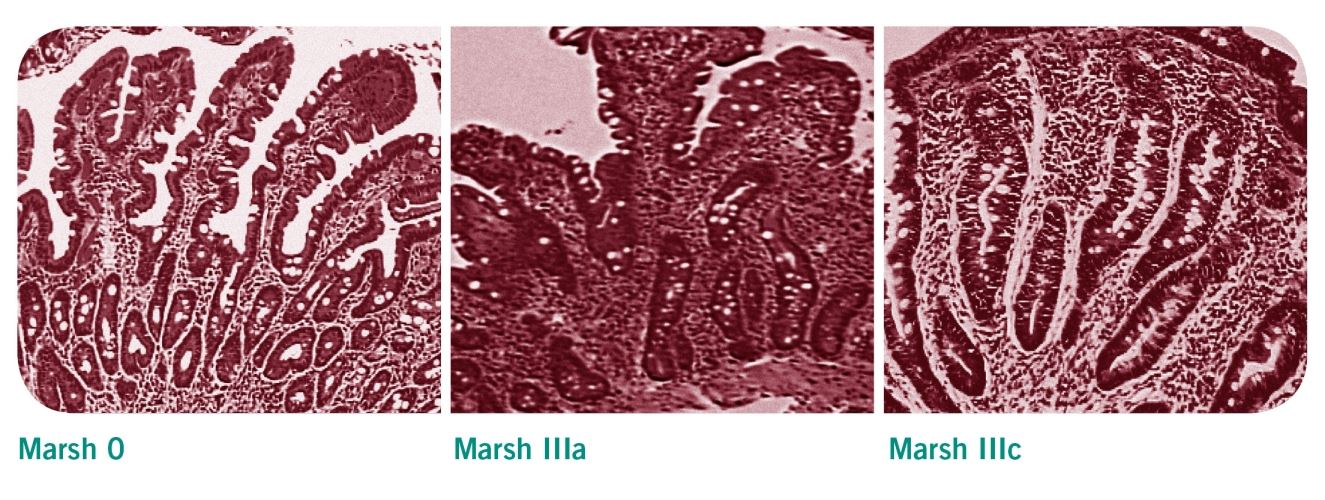

III. Histological tests

Patients with positive serological test results should be referred to a gastrointestinal specialist for endoscopic intestinal biopsy to confirm or exclude coeliac disease [2]. Villous atrophy may be patchy in coeliac disease, therefore a mimimum of four biopsy specimens should be obtained, including a duodenal bulb biopsy [1]. The histological changes observed in these samples are classified according to the Marsh classification. Evidence of villous atrophy and increased intraepithelial lymphocytes are typical features of a coeliac-positive histology (Marsh 3a-c).

Modified March criteria for the histological diagnosis of coeliac disease [5]

| Marsh classification | histological findings |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Normal duodenal mucosa |

| Stage 1 | Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) >25 IELs/100 enterocytes (non-specific finding) |

| Stage 2 | Stage 1 plus crypt hyperplasia (non-specific finding) |

| Stage 3a | Increased IELs, crypt hyperplasia, and partial villous atrophy |

| Stage 3b | Increased IELs, crypt hyperplasia, and subtotal villous atrophy |

| Stage 3c | Increased IELs, crypt hyperplasia, and total villous atrophy |

Biopsies for children?

Recently, the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) proposed new guidance regarding the diagnosis of coeliac disease in children [6]. ESPGHAN suggest that in symptomatic children, in whom the IgA tTG level exceeds 10 times the upper limit of normal, EMA antibodies are positive on a separately taken blood sample, and HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 are positive, then biopsies do not need to be performed to confirm a diagnosis of coeliac disease. Although this approach remains controversial, the British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN), together with Coeliac UK, have since published a joint guideline supporting ESPGHAN’s approach to the diagnosis of coeliac disease in children [7].

IV. Response to a gluten-free diet

The diagnosis of coeliac disease is considered to be confirmed if symptoms improve and repeat serological testing indicates that the antibodies are responding to the gluten-free diet. Current NICE guidelines on the Recognition, Assessment and Management of Coeliac Disease [2] recommend that patients with persistently high serolological titres or persistent symptoms after 12 months (where the possibility of continued gluten exposure has been excluded) should be considered for repeat intestinal biopsy and review by a specialist gastroenterology team.

Regular follow-up examinations

Guidelines from the Primary Care Society for Gastroenterology (PCSG) [8] recommend that newly diagnosed patients should be reviewed after 3-6 months and annually thereafter in order to monitor compliance with and response to treatment, and evidence of disease complications. Patients should be offered access to specialist dietetic and nutritional advice as part of this review, during which symptoms may be reviewed alongside dietary adherence, nutritional adequacy, and collection of anthropometrical data [2]. Repeat serological testing may be used in conjunction with dietetic review in order to assess adherence. Follow-up biopsies are not routinely used in the review of patients with coeliac disease but may be useful for patients whose condition does not respond to a gluten free diet [1].

References

- Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease : guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 2014; 63(8):1210-28

- NICE Guideline NG20: Recognition, Assessment & Management of Coeliac Disease. National Institute of Clinical Excellence 2015.

- Polvi A, Arranz E, Fernandez-Arquero M et al. HLA-DQ2-negative celiac disease in Finland and Spain. Hum Immunol 1998;59:169-75

- Abadie V, Sollid LM, Barreiro LB et al. Integration of genetic and immunological insights into a model of celiac disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol 2011; 29:493-525

- Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 11:1185-94

- Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 54: 136-160

- Murch S, Jenkins H, Auth M et al. Joint BSPGHAN and Coeliac UK guidelines for the diagnosis and management of coeliac disease in children. Arch Dis Child 2013 98: 806-811.

- The Management of Adults with Coeliac Disease in Primary Care. Primary Care Society for Gastroenterology 2006.

Further information on this topic

Studies

6

Show all

A Retrospective Application of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease in New Zealand Children.

In 2012 the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) published an updated guideline for the diagnosis of Coeliac disease, proposing a non-biopsy based diagnostic approach for a proportion of symptomatic children where appropriate serology (tTG IgA level at least 10 times upper limit of normal and positive EMA) and 'at risk' genotype (HLA DQ2 or DQ8) was evident. This retrospective study aimed to assess the applicability of this guideline to children in New Zealand. Children less than 16 years of age investigated for coeliac disease with small bowel biopsy in between January 2010 and December 2012 were identified. The results of those with tissue transglutaminase IgA (tTG) levels greater than 50 units (10 times upper limit of normal), positive endomysial antibodies and HLA DQ2/DQ8 were used to calculate sensitivity and specificity. Data from 160 children was available: 70 had biopsy-confirmed Coeliac disease, and 90 had negative biopsies. Limited data relating to HLA DQ2/DQ8 testing precluded application of the guidelines to all patients. However, the isolated use of the anti-tTG antibody cut off of 10 times the upper limit of normal generated a sensitivity of 67% and moderately high specificity of 92%. Specificity increased to 97% when limited EMA and HLA DQ2/DQ8 data was added. data, levels above 50 units and a specificity of 92%. Specificity increased to 97% when limited EMA and HLA DQ2/DQ8 data was added. A potential 67% reduction in the number of diagnostic biopsies performed would significantly reduce the work load and cost to the health system along with inconvenience and stress to families. However, it is important to avoid incorrect diagnosis of coeliac disease - if this current study is representative of the local population, up to three children out of every hundred investigated for coeliac disease could be falsely diagnosed. The limited amount of data was a major limitation of this study, therefore the value of the 2012 ESPGHAN guideline for the diagnosis of coeliac disease should now be evaluated prospectively.

Resource: International Journal of Coeliac Disease, Dec 2014 (vol 2; no. 4)

Resource: International Journal of Coeliac Disease, Dec 2014 (vol 2; no. 4)

Coeliac disease: The debate on coeliac disease screening - are we there yet?

The majority of patients with coeliac disease are undiagnosed, leading to debate about the utility of screening. The heterogeneous clinical presentation, which includes asymptomatic forms, can partially explain the difficulties faced when identifying coeliac disease. Now, Kurppa and colleagues add another element to the debate by strengthening the arguments for general screening.

Resource: Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology Volume: 11, Pages: 457–458 201

Resource: Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology Volume: 11, Pages: 457–458 201

Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology

ABSTRACT

A multidisciplinary panel of 18 physicians and 3 non-physicians from eight countries (Sweden, UK, Argentina, Australia, Italy, Finland, Norway and the USA) reviewed the literature on diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease (CD).

This paper presents the recommendations of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Areas of controversies were explored through phone meetings and web surveys. Nine working groups examined the following areas of CD diagnosis and management: classification of CD; genetics and immunology; diagnostics; serology and endoscopy; follow-up; gluten-free diet; refractory CD and malignancies; quality of life; novel treatments; patient support; and screening for CD.

Resource: Gut doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578

Jonas F Ludvigsson, Julio C Bai, Federico Biagi, Timothy R Card, Carolina Ciacci, Paul J Ciclitira, Peter H R Green, Marios Hadjivassiliou, Anne Holdoway, David A van Heel, Katri Kaukinen, Daniel A Leffler, Jonathan N Leonard, Knut E A Lundin, Norma McGough, Mike Davidson, Joseph A Murray, Gillian L Swift, Marjorie M Walker, Fabiana Zingone, David S Sanders, Authors of the BSG Coeliac Disease Guidelines Development Group

A multidisciplinary panel of 18 physicians and 3 non-physicians from eight countries (Sweden, UK, Argentina, Australia, Italy, Finland, Norway and the USA) reviewed the literature on diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease (CD).

This paper presents the recommendations of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Areas of controversies were explored through phone meetings and web surveys. Nine working groups examined the following areas of CD diagnosis and management: classification of CD; genetics and immunology; diagnostics; serology and endoscopy; follow-up; gluten-free diet; refractory CD and malignancies; quality of life; novel treatments; patient support; and screening for CD.

Resource: Gut doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578

Jonas F Ludvigsson, Julio C Bai, Federico Biagi, Timothy R Card, Carolina Ciacci, Paul J Ciclitira, Peter H R Green, Marios Hadjivassiliou, Anne Holdoway, David A van Heel, Katri Kaukinen, Daniel A Leffler, Jonathan N Leonard, Knut E A Lundin, Norma McGough, Mike Davidson, Joseph A Murray, Gillian L Swift, Marjorie M Walker, Fabiana Zingone, David S Sanders, Authors of the BSG Coeliac Disease Guidelines Development Group

Serological Assessment for Celiac Disease in IgA Deficient Adults

Abstract

Purpose: Selective immunoglobulin A deficiency is the most common primary immunodeficiency disorder that is strongly overrepresented among patients with celiac disease (CD). IgG antibodies against tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and deamidated gliadin peptides (DGP) serve as serological markers for CD in IgA deficient individuals, although the diagnostic value remains uncertain. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of these markers in a large cohort of IgA deficient adults with confirmed or suspected CD and relate the findings to gluten free diet.

Methods: Sera from 488,156 individuals were screened for CD in seven Swedish clinical immunology laboratories between 1998 and 2012. In total, 356 out of 1,414 identified IgA deficient adults agreed to participate in this study and were resampled. Forty-seven IgA deficient blood donors served as controls. Analyses of IgG antibodies against tTG and DGP as well as HLA typing were performed and a questionnaire was used to investigate adherence to gluten free diet. Available biopsy results were collected.

Results: Out of the 356 IgA deficient resampled adults, 67 (18.8%) were positive for IgG anti-tTG and 79 (22.2%) for IgG anti-DGP, 54 had biopsy confirmed CD. Among the 47 IgA deficient blood donors, 4 (9%) were positive for IgG anti-tTG and 8 (17%) for anti-DGP. Four were diagnosed with biopsy verified CD, however, 2 of the patients were negative for all markers. Sixty-eight of 69 individuals with positive IgG anti-tTG were HLA-DQ2/DQ8 positive whereas 7 (18.9%) of the 37 individuals positive for IgG anti-DGP alone were not.

Conclusions: IgG anti-tTG seems to be a more reliable marker for CD in IgA deficient adults whereas the diagnostic specificity of anti-DGP appears to be lower. High levels of IgG antibodies against tTG and DGP were frequently found in IgA deficient adults despite adhering to gluten free diet.

Resource: PLOS ONE, 9 April 2014, Vol 9, Issue 4 (www.plosone.org)

Purpose: Selective immunoglobulin A deficiency is the most common primary immunodeficiency disorder that is strongly overrepresented among patients with celiac disease (CD). IgG antibodies against tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and deamidated gliadin peptides (DGP) serve as serological markers for CD in IgA deficient individuals, although the diagnostic value remains uncertain. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of these markers in a large cohort of IgA deficient adults with confirmed or suspected CD and relate the findings to gluten free diet.

Methods: Sera from 488,156 individuals were screened for CD in seven Swedish clinical immunology laboratories between 1998 and 2012. In total, 356 out of 1,414 identified IgA deficient adults agreed to participate in this study and were resampled. Forty-seven IgA deficient blood donors served as controls. Analyses of IgG antibodies against tTG and DGP as well as HLA typing were performed and a questionnaire was used to investigate adherence to gluten free diet. Available biopsy results were collected.

Results: Out of the 356 IgA deficient resampled adults, 67 (18.8%) were positive for IgG anti-tTG and 79 (22.2%) for IgG anti-DGP, 54 had biopsy confirmed CD. Among the 47 IgA deficient blood donors, 4 (9%) were positive for IgG anti-tTG and 8 (17%) for anti-DGP. Four were diagnosed with biopsy verified CD, however, 2 of the patients were negative for all markers. Sixty-eight of 69 individuals with positive IgG anti-tTG were HLA-DQ2/DQ8 positive whereas 7 (18.9%) of the 37 individuals positive for IgG anti-DGP alone were not.

Conclusions: IgG anti-tTG seems to be a more reliable marker for CD in IgA deficient adults whereas the diagnostic specificity of anti-DGP appears to be lower. High levels of IgG antibodies against tTG and DGP were frequently found in IgA deficient adults despite adhering to gluten free diet.

Resource: PLOS ONE, 9 April 2014, Vol 9, Issue 4 (www.plosone.org)

Coeliac Patients Are Undiagnosed at Routine Upper Endoscopy

Abstract

Background and Aims

Two out of three patients with Coeliac Disease (CD) in Australia are undiagnosed. This prospective clinical audit aimed to determine how many CD patients would be undiagnosed if duodenal biopsy had only been performed if the mucosa looked abnormal or the patient presented with typical CD symptoms.

Methods

All eligible patients presenting for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (OGD) in a regional center from 2004–2009 underwent prospective analysis of presenting symptoms and duodenal biopsy. Clinical presentations were defined as either Major (diarrhea, weight loss, iron deficiency, CD family history or positive celiac antibodies- Ab) or Minor Clinical Indicators (CI) to duodenal biopsy (atypical symptoms). Newly diagnosed CD patients had follow up celiac antibody testing.

Results

Thirty-five (1.4%) new cases of CD were identified in the 2,559 patients biopsied at upper endoscopy. Almost a quarter (23%) of cases presented with atypical symptoms. There was an inverse relationship between presentation with Major CI’s and increasing age (<16, 16–59 and >60: 100%, 81% and 50% respectively, p = 0.03); 28% of newly diagnosed CD patients were aged over 60 years. Endoscopic appearance was a useful diagnostic tool in only 51% (18/35) of CD patients. Coeliac antibodies were positive in 34/35 CD patients (sensitivity 97%).

Conclusions

Almost one quarter of new cases of CD presented with atypical symptoms and half of the new cases had unremarkable duodenal mucosa. At least 10% of new cases of celiac disease are likely to be undiagnosed at routine upper endoscopy, particularly patients over 60 years who more commonly present atypically. All new CD patients could be identified in this study by performing pre-operative celiac antibody testing on all patients presenting for OGD and proceeding to biopsy only positive antibody patients and those presenting with either Major CI or abnormal duodenal mucosa for an estimated cost of AUS$4,629 and AUS$3,710 respectively.

Resource: PLOS ONE, March 2014, Vol 9, Issue 3 (www.plosone.org)

Background and Aims

Two out of three patients with Coeliac Disease (CD) in Australia are undiagnosed. This prospective clinical audit aimed to determine how many CD patients would be undiagnosed if duodenal biopsy had only been performed if the mucosa looked abnormal or the patient presented with typical CD symptoms.

Methods

All eligible patients presenting for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (OGD) in a regional center from 2004–2009 underwent prospective analysis of presenting symptoms and duodenal biopsy. Clinical presentations were defined as either Major (diarrhea, weight loss, iron deficiency, CD family history or positive celiac antibodies- Ab) or Minor Clinical Indicators (CI) to duodenal biopsy (atypical symptoms). Newly diagnosed CD patients had follow up celiac antibody testing.

Results

Thirty-five (1.4%) new cases of CD were identified in the 2,559 patients biopsied at upper endoscopy. Almost a quarter (23%) of cases presented with atypical symptoms. There was an inverse relationship between presentation with Major CI’s and increasing age (<16, 16–59 and >60: 100%, 81% and 50% respectively, p = 0.03); 28% of newly diagnosed CD patients were aged over 60 years. Endoscopic appearance was a useful diagnostic tool in only 51% (18/35) of CD patients. Coeliac antibodies were positive in 34/35 CD patients (sensitivity 97%).

Conclusions

Almost one quarter of new cases of CD presented with atypical symptoms and half of the new cases had unremarkable duodenal mucosa. At least 10% of new cases of celiac disease are likely to be undiagnosed at routine upper endoscopy, particularly patients over 60 years who more commonly present atypically. All new CD patients could be identified in this study by performing pre-operative celiac antibody testing on all patients presenting for OGD and proceeding to biopsy only positive antibody patients and those presenting with either Major CI or abnormal duodenal mucosa for an estimated cost of AUS$4,629 and AUS$3,710 respectively.

Resource: PLOS ONE, March 2014, Vol 9, Issue 3 (www.plosone.org)

Celiac disease: diagnosis and management.

Abstract

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. It is triggered by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. Gluten is a storage protein in wheat, rye, and barley, which are staples in many American diets. Celiac disease is characterized by chronic inflammation of the small intestinal mucosa, which leads to atrophy of the small intestinal villi and subsequent malabsorption. The condition may develop at any age. Intestinal manifestations include diarrhea and weight loss. Common extraintestinal manifestations include iron deficiency anemia, decreased bone mineral density, and neuropathy. Most cases of celiac disease are diagnosed in persons with extraintestinal manifestations. The presence of dermatitis herpetiformis is pathognomonic for celiac disease. Diagnosis is supported by a positive tissue transglutaminase serologic test but, in general, should be confirmed by a small bowel biopsy showing the characteristic histology associated with celiac disease. The presence of human leukocyte antigen alleles DQ2, DQ8, or both is essential for the development of celiac disease, and can be a useful genetic test in select instances. Treatment of celiac disease is a gluten-free diet. Dietary education should focus on identifying hidden sources of gluten, planning balanced meals, reading labels, food shopping, dining out, and dining during travel. About 5% of patients with celiac disease are refractory to a gluten-free diet. These patients should be referred to a gastroenterologist for reconsideration of the diagnosis or for aggressive treatment of refractory celiac disease, which may involve corticosteroids and immunomodulators.

Resource: Am Fam Physician. 2014 Jan 15;89(2):99-105.

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. It is triggered by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. Gluten is a storage protein in wheat, rye, and barley, which are staples in many American diets. Celiac disease is characterized by chronic inflammation of the small intestinal mucosa, which leads to atrophy of the small intestinal villi and subsequent malabsorption. The condition may develop at any age. Intestinal manifestations include diarrhea and weight loss. Common extraintestinal manifestations include iron deficiency anemia, decreased bone mineral density, and neuropathy. Most cases of celiac disease are diagnosed in persons with extraintestinal manifestations. The presence of dermatitis herpetiformis is pathognomonic for celiac disease. Diagnosis is supported by a positive tissue transglutaminase serologic test but, in general, should be confirmed by a small bowel biopsy showing the characteristic histology associated with celiac disease. The presence of human leukocyte antigen alleles DQ2, DQ8, or both is essential for the development of celiac disease, and can be a useful genetic test in select instances. Treatment of celiac disease is a gluten-free diet. Dietary education should focus on identifying hidden sources of gluten, planning balanced meals, reading labels, food shopping, dining out, and dining during travel. About 5% of patients with celiac disease are refractory to a gluten-free diet. These patients should be referred to a gastroenterologist for reconsideration of the diagnosis or for aggressive treatment of refractory celiac disease, which may involve corticosteroids and immunomodulators.

Resource: Am Fam Physician. 2014 Jan 15;89(2):99-105.

A Retrospective Application of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease in New Zealand Children.

In 2012 the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatolog...

Coeliac disease: The debate on coeliac disease screening - are we there yet?

The majority of patients with coeliac disease are undiagnosed, leading...

Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology

ABSTRACT

A multidisciplinary panel of 18 physicians and 3 non-physi...

Serological Assessment for Celiac Disease in IgA Deficient Adults

Abstract

Purpose: Selective immunoglobulin A deficiency is the most...

Coeliac Patients Are Undiagnosed at Routine Upper Endoscopy

Abstract

Background and Aims

Two out of three patients with Coelia...

Celiac disease: diagnosis and management.

Abstract

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder of the gastrointe...

www.drschaer-institute.com