FODMAPs: food composition, defining cut-off values and international application

Varney J, Barrett J, Scarlata K et al

Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2017; 32(suppl.1) 53-61

The benefits of a low-FODMAP diet in people with IBS are now well established. The Monash University Department of Gastroenterology has performed extensive work for over 10 years to quantify the FODMAP composition of hundreds of foods. This review paper discusses the criteria for classifying food as low in FODMAPs and the challenges encountered in analysing food for FODMAP content.

Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2017; 32(suppl.1) 53-61

The benefits of a low-FODMAP diet in people with IBS are now well established. The Monash University Department of Gastroenterology has performed extensive work for over 10 years to quantify the FODMAP composition of hundreds of foods. This review paper discusses the criteria for classifying food as low in FODMAPs and the challenges encountered in analysing food for FODMAP content.

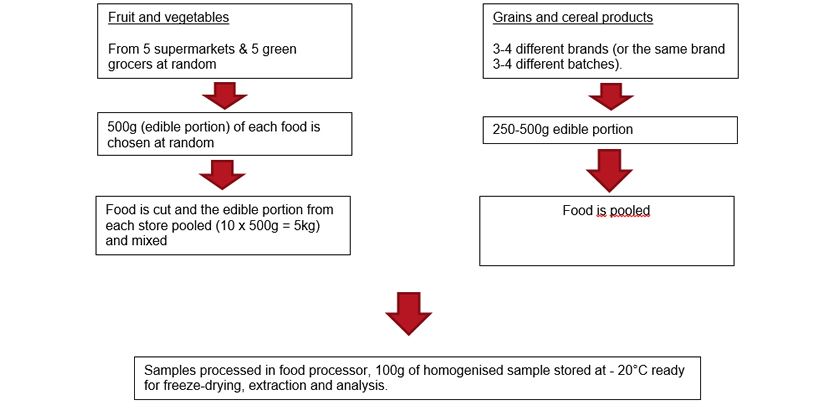

FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, and mono-saccharides and polyols) include lactose, fructose in excess of glucose, sugar polyols (sorbitol and mannitol), fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS – stachyose and raffinose). The techniques for quantifying FODMAP levels in foods are briefly summarised in the flow diagram on the right.

Using the techniques developed by Monash University, the FODMAP content of a large number of fruits, vegetables, grain and cereals has been published 1-3.

Low-FODMAP cut-off values

In order to fully develop the low-FODMAP diet concept, the establishment of cut-off values to classify foods as low-FODMAP are essential, these are provided in the table below. These cut-off values relate to each particular FODMAP sugar present in a food. Cut-off values were derived by considering the FODMAP content and typical serving size of food consumed in a single sitting that commonly triggers symptoms in IBS sufferers. These levels are set conservatively to allow people to include a number of low-FODMAP foods at each sitting.

The reliability of these FODMAP cut-off values has been tested and confirmed in a number of studies with an upper limit of 0.5g total FODMAPs (excluding lactose) per sitting being applied to the low-FODMAP arm of each study. The most recent of these studies was the landmark randomised control trial which demonstrated that a low-FODMAP diet improved functional gastrointestinal symptoms in people with IBS4. This study utilised the cut-off values presented here in order to design diets low and high in FODMAPs. Examples of high-FODMAP foods omitted from the low-FODMAP diet in this trial included: honey, apples, pears, watermelon, stone fruit, onion, leek, asparagus, artichokes, legumes, lentils, cabbage, brussel sprouts, wheat- and rye-based breads, pasta, breakfast cereals, cakes and biscuits.

Determining tested cut-off values for low FODMAP foods has enabled the Monash team to make FODMAP composition data available worldwide via their smart phone application, using a traffic light system to indicate the suitability of foods for a low-FODMAP diet.

Impact of ingredient selection and food processing on FODMAP content

A number of ingredients and food processing techniques may influence the final FODMAP composition of processed foods. As a result, it can be inaccurate to predict whether a product will be low or high in FODMAPs based purely on the ingredient list and without direct analysis of the product. Ingredients that commonly influence the final FODMAP content include flours, grains, sweetening agents and inulin. Inter-country differences in the fructan content of locally grown grain, potentially influenced by growing conditions and plant cultivars may also impact on final FODMAP content.

Food processing techniques known to affect FODMAP levels include those that involve the addition of heat and water. Such processes may result in water-soluble FODMAPs (eg fructans and GOS) leaching into surrounding liquid, e.g. canned lentils are lower in GOS than boiled lentils, and firm (pressed) tofu contains less fructans and GOS than silken tofu (which is typically unpressed with a higher water content). A further example of the impact of food production methods on FODMAP content is observation that spelt sourdough bread is lower in FODMAP content than spelt flakes and pasta. The traditional sourdough lactobacilli fermentation process and longer proving time result in lowering the fructan content of the final product.

Implementing the low-FODMAP diet around the world

In order to facilitate further international uptake of the low-FODMAP diet, there is a need for more comprehensive country-specific FODMAP composition data to be made available. A number of country specific factors are known to influence the FODMAP content of foods, including unique food processing techniques and labelling regulation, food supply, culture and eating habits. For example, in the USA, the wide use of high-fructose corn syrup in processed foods has contributed to the observation that US breads often contain more excess fructose than those sold in Australia. Furthermore, high-FODMAP ingredients such as onion and garlic are not always clearly labelled within ingredients lists, with the terms ‘flavoring” and “spices” considered acceptable alternatives according to USDA regulations. Also of relevance to certain countries, including the USA is the tendency towards larger portion sizes and heavy reliance of take-away meals and pre-prepared convenience meals, the FODMAP composition of which is often unknown.

References:

Using the techniques developed by Monash University, the FODMAP content of a large number of fruits, vegetables, grain and cereals has been published 1-3.

Low-FODMAP cut-off values

In order to fully develop the low-FODMAP diet concept, the establishment of cut-off values to classify foods as low-FODMAP are essential, these are provided in the table below. These cut-off values relate to each particular FODMAP sugar present in a food. Cut-off values were derived by considering the FODMAP content and typical serving size of food consumed in a single sitting that commonly triggers symptoms in IBS sufferers. These levels are set conservatively to allow people to include a number of low-FODMAP foods at each sitting.

| Individual FODMAPs | Grams per serve (individual food) |

| Oligosaccharides (core grain products, legumes, nuts and seeds) | <0.30 |

| Oligosaccharides (vegetables, fruits, and all other products) | <0.20 |

| Polyols – sorbitol or mannitol | <0.20 |

| Total polyols | <0.40 |

| Excess fructose | <0.15 |

| Excess fructose (for fresh fruit and vegetables when “fructose in excess of glucose” is the only FODMAP present) | <0.40 |

| Lactose | <1.00 |

The reliability of these FODMAP cut-off values has been tested and confirmed in a number of studies with an upper limit of 0.5g total FODMAPs (excluding lactose) per sitting being applied to the low-FODMAP arm of each study. The most recent of these studies was the landmark randomised control trial which demonstrated that a low-FODMAP diet improved functional gastrointestinal symptoms in people with IBS4. This study utilised the cut-off values presented here in order to design diets low and high in FODMAPs. Examples of high-FODMAP foods omitted from the low-FODMAP diet in this trial included: honey, apples, pears, watermelon, stone fruit, onion, leek, asparagus, artichokes, legumes, lentils, cabbage, brussel sprouts, wheat- and rye-based breads, pasta, breakfast cereals, cakes and biscuits.

Determining tested cut-off values for low FODMAP foods has enabled the Monash team to make FODMAP composition data available worldwide via their smart phone application, using a traffic light system to indicate the suitability of foods for a low-FODMAP diet.

Impact of ingredient selection and food processing on FODMAP content

A number of ingredients and food processing techniques may influence the final FODMAP composition of processed foods. As a result, it can be inaccurate to predict whether a product will be low or high in FODMAPs based purely on the ingredient list and without direct analysis of the product. Ingredients that commonly influence the final FODMAP content include flours, grains, sweetening agents and inulin. Inter-country differences in the fructan content of locally grown grain, potentially influenced by growing conditions and plant cultivars may also impact on final FODMAP content.

Food processing techniques known to affect FODMAP levels include those that involve the addition of heat and water. Such processes may result in water-soluble FODMAPs (eg fructans and GOS) leaching into surrounding liquid, e.g. canned lentils are lower in GOS than boiled lentils, and firm (pressed) tofu contains less fructans and GOS than silken tofu (which is typically unpressed with a higher water content). A further example of the impact of food production methods on FODMAP content is observation that spelt sourdough bread is lower in FODMAP content than spelt flakes and pasta. The traditional sourdough lactobacilli fermentation process and longer proving time result in lowering the fructan content of the final product.

Implementing the low-FODMAP diet around the world

In order to facilitate further international uptake of the low-FODMAP diet, there is a need for more comprehensive country-specific FODMAP composition data to be made available. A number of country specific factors are known to influence the FODMAP content of foods, including unique food processing techniques and labelling regulation, food supply, culture and eating habits. For example, in the USA, the wide use of high-fructose corn syrup in processed foods has contributed to the observation that US breads often contain more excess fructose than those sold in Australia. Furthermore, high-FODMAP ingredients such as onion and garlic are not always clearly labelled within ingredients lists, with the terms ‘flavoring” and “spices” considered acceptable alternatives according to USDA regulations. Also of relevance to certain countries, including the USA is the tendency towards larger portion sizes and heavy reliance of take-away meals and pre-prepared convenience meals, the FODMAP composition of which is often unknown.

References:

- Muir JG, Shepherd SJ, Rosella O et al. Fructan and free fructose content of common Australian vegetables and fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007; 55: 6619–6627.

- Muir JG, Rose R, Rosella O et al. Measurement of short-chain carbohydrates in common Australian vegetables and fruits by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009; 57: 554–565.

- Biesiekierski JR, Rosella O, Rose R et al. Quantification of fructans, galacto-oligosacharides and other short-chain carbohydrates in processed grains and cereals. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011; 24: 154–176

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ et al. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: 67–75 .e5

www.drschaer-institute.com